If onions make you cry, are there vegetables that make you happy? Is a harp just a nude piano? Is a vacuum cleaner a broom with a stomach? Is mauve simply pink trying to be purple? Do dogs do it “people-style”? And why is there no other word for synonym?

Welcome to the literal, lateral mind of the child with Asperger’s syndrome. My new novel, The Boy Who Fell To Earth, is about a single mother, Lucy, raising a boy on the autism spectrum. She often feels that she didn’t give birth to him at all, but found him under a spaceship and simply raised him as her own. The book could have been called My Family And Other Aliens.

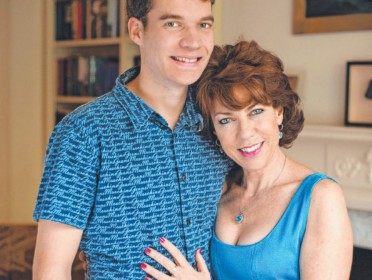

Even though my book is fictional (my own husband is loving and supportive), it’s rooted in reality as my own son was diagnosed with Asperger’s, aged three. He is now 21. I am speaking about this for the first time with his blessing. Julius hopes the novel will help de-stigmatise the condition and, in his own words, “make people more understanding and less judgmental”.

I, too, hope that the novel will be seen as a celebration of eccentricity, idiosyncrasies and difference.

A jigsaw puzzle

Before Julius was born, all I knew about autism was that it was a lifelong neurological disorder chiefly characterised by an inability to communicate effectively, plus inappropriate or obsessive behaviour.

I now know that it means not getting a joke, not knowing what to say – then saying the wrong things. It means being told off but not understanding why, doing your best but still getting it wrong, feeling confused, frightened, out of sync: all day, every day.

I know that people treat you as though you’re a rare, feral creature recently netted and still adjusting to captivity, and that venturing out of the house can feel as hazardous as Scott leaving his Antarctic base camp.

Is it any wonder I became overprotective? All through Jules’s teens, every time he walked out of the door, you’d think he was emigrating. The fuss, the long hugs and heartfelt goodbyes. But how will you ever know if your child can cope in the outside world, if you never let him into it?

I have seen mothers tearing their hair out over sugar content and how to make broccoli fun. But mothering a child with Asperger’s is like trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle without the benefit of a coloured picture on the box. Social workers tell my protagonist that being the mother of such a child will be a challenge, but an exciting one. This is as accurate as the Titanic’s captain telling his passengers they’re in for a diverting dip in the briny.

Social isolation

As well as giving insight into my own and Julius’s experiences, the book is also a tribute to all the inspirational parents who have shared with me their battles against bureaucracy, while bankrupting themselves trying to get the right medical advice.

The mother of a special needs child has to be his legal advocate – fighting in his educational corner; full-time scientist – challenging doctors and questioning medications; executive officer – making difficult decisions on his behalf; and bodyguard against the taunts of other children.

Raising a child with special needs is also socially isolating. As Lucy discovers, the playground sandbox invariably becomes a quicksand box, as other parents, fearing some AIDS-like contagion, abandon you. Unusual behaviour is criticised by shop owners as bad parenting, with a reprimand that you’ve raised a “spoilt brat”. You learn that embarrassment is a luxury not afforded to you.

People with Asperger’s, or “Asparagus syndrome” as Jules calls it, have no filter and tend to say what they are thinking. My son once inquired of a surly, tattooed bikie if he’d ever noticed that his chin looked like upside down testicles?

Perplexing responses

Such candour not only has me sweating more than Paris Hilton doing a Sudoku puzzle but it can also be dangerous.

I was taking our daughter Georgie to drama class and asked Jules, then 13, to lock the door before he went out to play, as burglars might steal my jewellery. When we came home to find the door ajar, Jules explained, perplexed, “Well, why would men want jewellery?”. When Georgie says, “You’ll have to fight me for the last cupcake”, he squares up.

But one thing is certain: sending your special-needs child to a normal school is as pointless as giving a fish a bath. The system is designed with bureaucratic speed bumps to slow a parent’s progress. I filled in forests of forms and saw squadrons of “experts”, all of whom look down their noses for a living. The technical term for this process is “being passed from pillar to post”.

Most kids strive to learn math and grammar: Aspergic children strive to make themselves invisible. But special schools have long waiting lists which means endless lobbying and pleading with the local council to meet your child’s educational needs.

For years, I trekked everywhere in the endless search for the right school for my son. He had so many tests and psychological and medical assessments, he must have thought he was being drafted into an elite astronaut program. It was only when we sent him, aged 16, to a private special needs college in America that we saw him thrive.

A chance to flourish

In the scramble for funds, kids with less obvious disabilities such as Asperger’s or autism often lose out. They may not be in a wheelchair, but they still deserve our help and the promise of a life not wasted. After all, creativity is associated with a variety of cognitive disorders. It’s believed that Mozart, Van Gogh, Orwell, Einstein and Warhol were on the autism spectrum.

People with Asperger’s may not contribute in conventional terms but that doesn’t make them less valuable: it’s up to us to help them flourish. My son is Wikipedia with a pulse. He knows more about Shakespeare, tennis stars and the Beatles than their own mothers.

A friend who has a son with Asperger’s worries that when he’s in his room, he’s accidentally hacking into a Pentagon computer while looking for the existence of UFOs and he’ll serve a jail sentence for cyber terrorism – yet this same whiz kid can’t get the right change from the local shop.

Life with Julius is challenging, but it’s also hilarious, humbling, and enriching. My kind, clever, quirky boy has grown into a handsome young man who is the most interesting and courageous person I’ve ever met.

With understanding, along with early educational intervention, these kids can fulfil their potential. Jules now volunteers for Oxfam and is working on becoming the world’s most colourful sports commentator.

People with Asperger’s often feel they’re drowning in their own brain waves. I hope this novel, in its own small way, acts as a literary life raft.

The Boy Who Fell To Earth, (Random House), is out now.

Source: bodyandSoul

We are sharing information for knowledge. Presented by. SocialDiary.Net

We are sharing information for knowledge. Presented by. SocialDiary.Net